So. Let’s talk about collaboration.

I think there are some misconceptions about this that need to be addressed up front. Otherwise we may gain too much comfort from watching characters like Daniel and Eleanor getting their comeuppance and don’t consider the broader problem. By no means am I defending the actions of these characters. But I do think we risk missing the point when we focus on the nastiest aspects of collaboration and fail to understand why or how this is happening. I know it sounds foolish but I do believe that a compassionate perspective is a valuable addition alongside criticism and disgust.

The first thing I want to point out is that within totalitarian regimes collaboration is actually very common. For example in Timothy Garton Ash’s highly thought provoking The File: A Personal History we discover that collaboration with the Stasi in East Germany was extremely widespread. The Stasi relied on hundreds of thousands of informants drawn from all sections of German society.

The notorious Stasi headquarters in Berlin, centre for East German oppression. At its height the Stasi had as many as 170,000 registered informants.

Garton Ash is a British historian who lived in East Germany as a student during the Cold War 1980s. In the late 90s he returned to Berlin, to examine his Stasi File, which was an option made available to Germans at the time as part of their own sort of truth and reconciliation programme.

What Garton Ash then did was track down and interview all those people named as informants in his file to ask them why. The responses he got were varied and fascinating.

What you find is less malice than human weakness, a vast anthology of human weakness. And when you talk to those involved, what you find is less deliberate dishonesty then our almost infinite capacity for self-deception.

If only I had met, on this search, a single clearly evil person.

The File: A Personal History by Timothy Garton Ash

(The File went on to influence the development of the excellent Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck film The Lives of Others. A must watch, not just for historical purposes. It’s just a good film.)

If I have any criticism of V it is that the writing for the collaborators is at times a little heavy handed. (Of course The Final Battle is particularly bad for this.) Things are not black and white and focusing too much attention on the characters in V who are malicious misses the true scale of the collective impact of collaborators who were motivated by self deception, pain or even love.

When you look at the characters from V more honestly you see that several who are the “goodies” are just as guilty of minor or major forms of collaboration. On a small scale various characters are compromised in their daily lives in a way that makes them go along with things like the war on science. People like Juliet’s boyfriend Denny, Stanley and even Sancho. On a larger scale Robert Maxwell collaborates when he is forced to inform on his own family (just like Daniel). Mike informs on Martin under the influence of truth serum (effectively while being tortured) and Father Andrew delivers Elizabeth straight into Diana’s clutches out of some misplaced belief in peace and goodwill.

Collaboration isn’t necessarily automatically evil. If you recall our discussion of our helpers a few weeks back you may have picked up that Denmark used collaboration in a unique way. Denmark was conquered in a matter of days and knew there was no point resisting their much stronger neighbour to the south. Initially they employed the characteristic Danish “leg godt” approach. (From whence the term for the popular children’s building brick toy derives.) But before you run out and throw away all your lego in ‘let’s cancel the Danes’ disgust, also remember that the Danes used collaboration to get away with all sorts of things like helping save 99% of their Jewish population from extermination. Denmark has a complicated history of collaboration on its conscience. It’s never as simple as right or wrong.

Then there are the women in France who had their heads shaved and were subject to public humiliation for fraternising with Germans. You may well think “good riddance they deserved it”. But before you harden your hearts too much, consider the characters in V who actually had liaisons with “the enemy”. How fair do you think it really would be to see Robin Maxwell, Harmony Moore or Maggie Blodgett treated in this way? I somehow doubt these mobs that gathered at the end of the war had much time for consideration of the peculiar niceties of each woman’s individual circumstances. And you have to ask the question why focus on these people? When so many others were friendly with Nazi occupiers as well?

Women in France who were identified as collaborators and paraded through the streets after having their heads shaven. Could it be misogyny? Surely not.

It is this that makes me slightly uncomfortable with the complete vilification of our collaborators that I regularly see on V fan forums. I do understand. It’s comforting to criticise, to hold people to account for their actions and to differentiate ourselves from them.

It’s true what people often say: we, who never faced these choices, can never know how we would have acted in their position, or would act in another dictatorship. So who are we to condemn? But equally, who are we to forgive?

The File: A Personal History by Timothy Garton Ash

Collaboration is like an insidious venom that poisons us all, good, bad, strong, weak. Dictatorships use it as a tool to compromise everyone and undermine the fabric of society.

It is with this in mind that I invite you to consider the following characters.

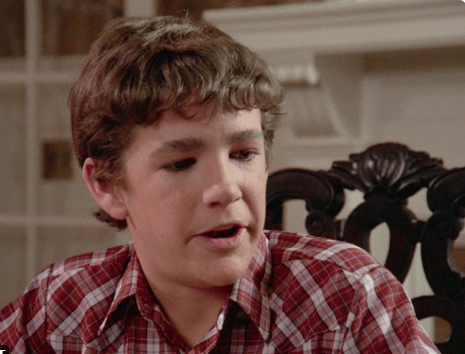

Daniel Bernstein (played by David Packer)

Why Daniel is excited by the arrival of the aliens from day one is an enduring puzzle in the show.

It’s a fact. Everyone loves to hate Daniel Bernstein. Daniel becomes ever more villainous as V progresses, but for him things started out a bit more ambiguously.

At the start of the piece Daniel is a lost little boy. He’s seventeen years old. He is not in school or university. He hasn’t taken up a trade. He seems to be going from one low paid job to another. He has a crush on the girl next door who sees him as part of the furniture. He’s unlucky in love and waiting for his life to start.

When the flying saucers first arrive he is the only person who is actually excited about it. Why this is is never really explained but perhaps it doesn’t need to be. There’s a telling line when he and Robin are sitting on the front lawn contemplating their fate. He says

“What do you think they’ll do first…”

Before Robin cuts him off with the more pressing thought that they might all be about to die. And that line has stuck with me for the longest time. Where was Daniel going with that? What did he think they were going to do?

This is most likely that potent mix of precociousness and naïveté that many teenagers his age possess. He is truly captivated by the aliens from the moment they arrive. Like it’s the very thing he’s been waiting for.

The aliens could just as easily be Elvis Presley, The Beatles or Star Wars, all things that have inspired fanatical devotion. Daniel represents the many boys who would have been inspired by the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) or HJ for short.

Taika Waititi did not do much historical research for Jojo Rabbit for creative reasons, and perhaps because he did not want add oxygen to the fascination with Nazis which is fair enough.

Membership in the HJ was compulsory. The parents of children who didn’t join often were arrested. The membership age range was much younger as well, boys signed up from the age of ten. Jojo Rabbit will have you believe that the HJ was all about killing rabbits and playing with live ammo.* But for the most part was more like Boy Scouts.

In his book A Child of Hitler about his time in the Hitlerjugend Alfons Heck remembers this time very fondly. And for girls the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM or German League of Maidens) was equally fun as they got to do many of the same things as the boys. (In fact I’ve met people who were in the BDM who said many girls were sad when they aged out because they had to stop all that to settle into a life of good Aryan domesticity and childbearing.)

Nazi indoctrination of children started very young, children began their inculcation at school. Alfons Heck points out that many children in Hitlerjugend did not have any memory of the Weimar Republic and were already exposed to Nazi ideology through the education system well before they even joined the HJ or BDM.

This is really quite different to how Daniel Bernstein is depicted in V. And yes the irony of him being Jewish is not lost on the audience. Members of the Visitor’s Friends join voluntarily and were a lot older. Maybe Johnson chose to make Daniel seventeen because he didn’t want to throw a story about a very young boy into the path of an angry audience, I’m not sure.

Poor Sean. He’s just a child helpless against the weapons of torture and persuasion in Diana’s arsenal.

More age appropriate is the character of Sean Donovan played by Eric Johnston. In V he has been subjected to some horrible technological brainwashing process. This amounts to the same thing as the socialisation of little children from a very young age.

Daniel is a teenager but his behaviour is often childish, like he hasn’t quite learned the rules of cause and effect yet. Again this is consistent with most teenagers I know who look grown up but every now and then do or say something incredibly stupid, thus revealing their inexperience. Add teenage frustrations to the mix (the girl I like doesn’t like me back) and you have a potent recipe for a naïve abuse of power.

The reality of the consequences of his actions hits Daniel Bernstein hard as he surveys his empty home.

Daniel is an early adopter for the Visitor youth movement which we can only assume would also eventually become compulsory. In fact he is much more akin to the brown shirts than the Hitlerjugend. I have already highlighted that brown shirts skewed young and Daniel represents so many of those young men discussed earlier wandering the streets of Munich and Ancient Rome spoiling for some action, some sense of importance, some yet to be realised desire to score loot.

A surplus population of young men with no sense of purpose or significance is a dangerous thing! Everyone needs a sense of meaning and belonging. Even rotten little collaborators.

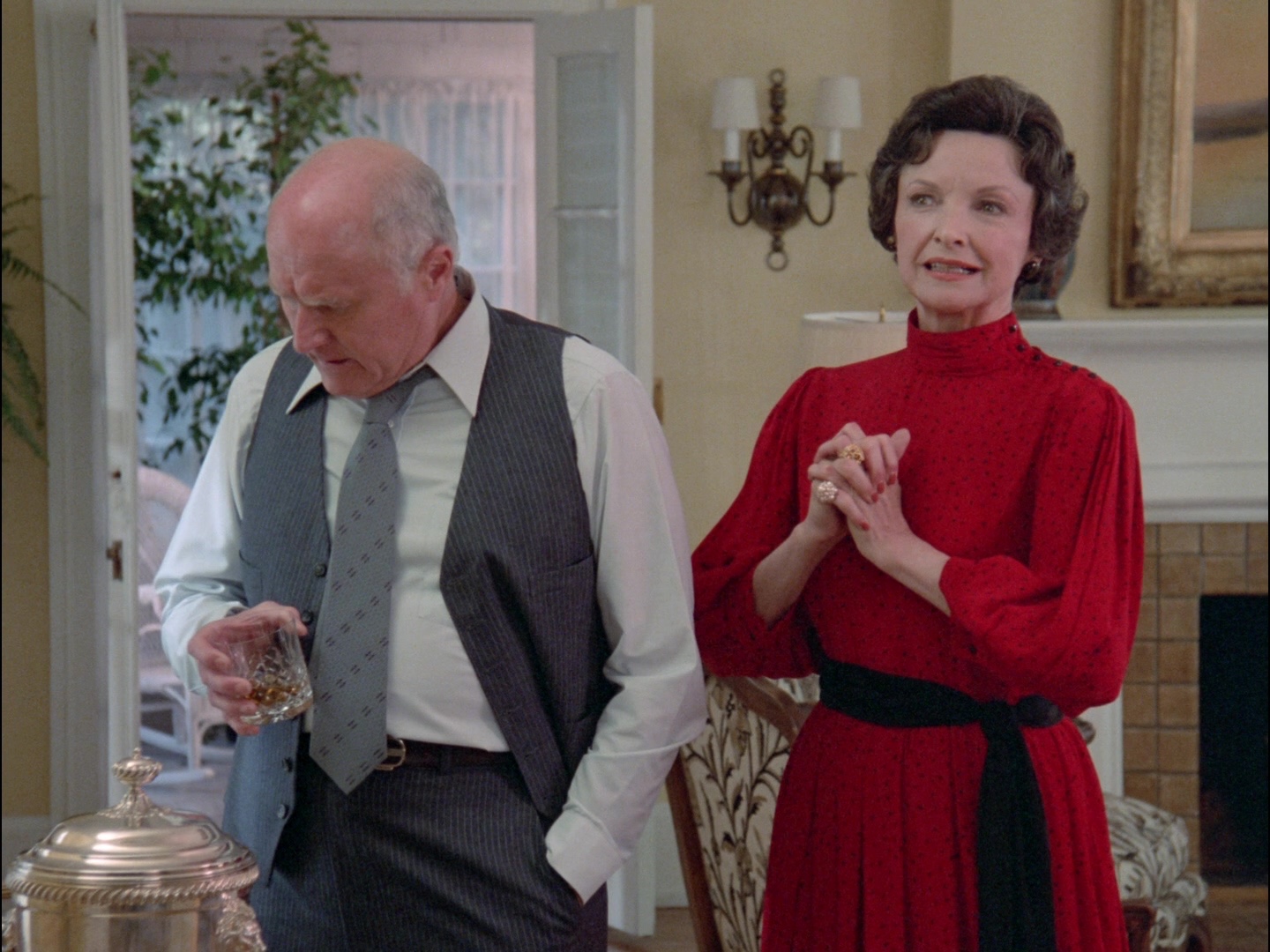

Eleanor Dupres (played by Neva Patterson)

Another character everyone loves to hate!

Eleanor Dupres plays Lady Macbeth to a weak-stomached alcoholic husband Arthur

Eleanor Durpes represents female collaboration with occupied forces. V tastefully stops just short of her having a sexual relationship with Visitor Gauleiter Steven – but only just. Perhaps with the age gap, and his character being a big lizard it was too racy to actually go there on air. (It’s now stunning to think that the idea of a post-menopausal woman having a sex life was possibly more shocking than lesbianism – see Diana and Kristine Walsh below)

When we first meet Eleanor she is married to chemical plant director Arthur Dupres. The couple are very comfortably well-off, apparently having navigated their way to the top of the heap in their small town in California. We can see it is Eleanor who is the brains of the pair. Eleanor is clearly a talented and intelligent woman who has had to live out her ambitions through the various men in her life because of her sex and the milieu into which she was born. She says as much when she tells her son Mike Donovan:

I’m a survivor Michael. Otherwise I wouldn’t have gotten here from that Louisiana hick town where I started.

Eleanor Dupres

To which her son protests “This is different!”

I’ve briefly mentioned before that things aren’t always rosy for a lot of people in our societies, mainly in relation to race and class, but for Eleanor it’s gender and class. And perhaps it’s hours of watching Mad Men but I do feel some sympathy for Eleanor and her lot in life as a woman coming up through the 50s and 60s. Can you blame her for taking control in what limited ways she can when her existence is dependent on often incompetent or uncaring men?

But Mike is right, there is a line between manipulating the system to survive, and profiting off the misery of others.

This is the face of a man watching the mother he once knew drift away into iniquity and greed.

I think this discussion with son Mike is extremely revealing. We confirm Eleanor is a social climber. But also that she is terrified of poverty. Particularly of the powerlessness that goes with poverty. She must have been a strong-willed woman to have raised Mike Donovan to become the man that he is today. But somewhere along the way survival turned to acquisitiveness. Eleanor bought her own hype. Maybe it’s this that drove her and her son apart. Mike is well brought up, and well educated but completely unpretentious. He doesn’t have time for the trappings of comfort and wealth that are so important to his mother. Ironically the very grit that gave her the determination to raise a strong son is that same thing that spoiled her, and made her repellent to him as well.

Eleanor represents those collaborators in society who were already fairly well off and went along with their oppressors because they had too much to lose. Coco Chanel springs to mind when I think of templates for this in the occupied territories. Chanel came from very humble origins very much like Eleanor Dupres. Chanel was an established French fashion icon during the 1930s. And when Paris was occupied in 1940 she quickly took up with Abwehr officer Baron Hans Günther von Dinklage. (Dincklage reported directly to Joseph Goebbels.) Chanel was an anti-Semite and has even been accused of going so far as to be an Abwehr spy. Of her collaboration her grand-niece said after the war:

You know, Mr. Vaughan, these were very difficult times, and people had to do very terrible things to get along.

Gabrielle Labrunie quoted in The New Yorker 31 August 2011

Coco Chanel is more famous for being a fashion leader. Less so for her Nazi collaboration.

It is clear Eleanor Dupres is supposed to be a parallel for all the aforementioned French women who had their heads shaved and were marched through town for all to see.

How did Coco Chanel escape this humiliating fate? Always the opportunist when the Americans liberated Paris she ran out and handed out Chanel No. 5 to passing G.I.s to take back to their girls. After liberation she fled to Switzerland where she lived for a decade before returning to France in the hope that enough time had passed for people to forgive and forget. And Chanel was a powerhouse of fashion for France which economically needed the brand. So yes perhaps not forgiven so much as reconciled.

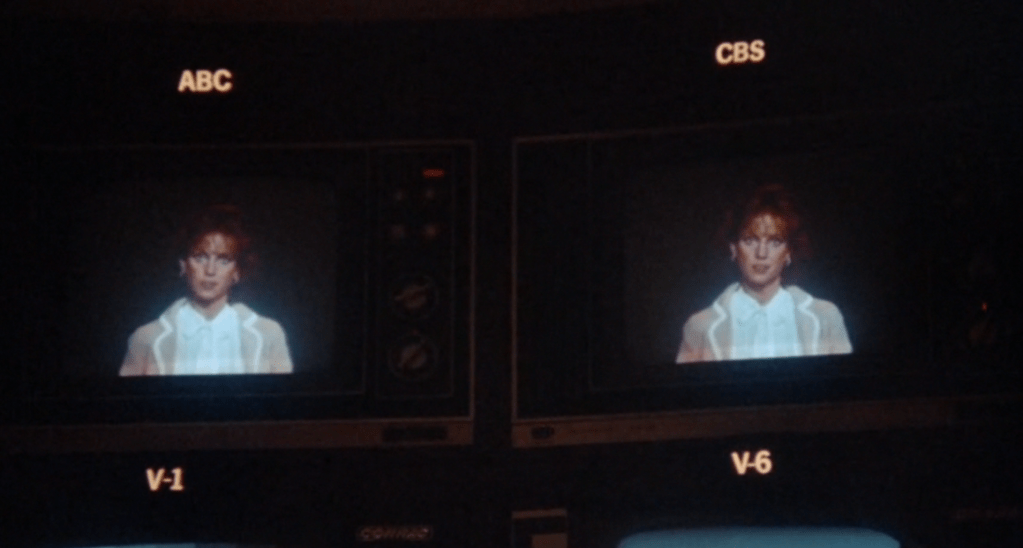

Kristine Walsh (played by Jenny Sullivan)

Kristine Walsh displays a stunning lack of any sense of self preservation as Diana holds her hand for a little too long while saying good night

Kristine Walsh is a representation of what happens when the personal ambitions of the members of the press overtake professional integrity.

Seizure and total control of the press was a key move undertaken by the Nazis during the rise to power. The line between journalism and propaganda is very quickly blurred with the introduction of “Aryanisation” of the press in 1934 (essentially eliminating Jewish journalists along with any who resisted)

In V we see the reduction of all news to a single outlet, a single source: The Visitor Press Secretary Kristine Walsh. Jenny Sullivan nails it with her delivery of this broadcasting persona. An attractive concerned looking woman signaling that it would be a terrible shame to disappoint our new friends the Visitors.

Kristine Walsh is ‘so very concerned’ about the state of the planet on so many different channels.

In Nazi Germany that outlet was the daily newspaper the Völkischer Beobachter. But Walsh bears little resemblance to Beobachter editor Alfred Rosenberg, or even Minister for Propaganda Joseph Goebbels.

If there’s anyone Kristine reminds me of, it’s director and film-maker Leni Riefenstahl who created Triumph of Will (which Alfons Heck reports was staple and highly repeated viewing for all the good little Nazis of the HJ).

Riefenstahl was a talented director who had a very close relationship with the Nazis. We are extremely visual and images have always been important historically. In the past most people were illiterate. Images tell effective stories for the illiterate whether through friezes on the Parthenon or stained glass windows in churches. So if you want to use propaganda, these existing traditions of art, architecture, design and film, are powerful megaphones. Riefenstahl’s images of crowds showing might and unity are incredibly effective, bringing a sense of belonging or dread to the viewer depending on whether you were included in the German Volk or not.

Leni Riefenstahl at work filming the iconic 1936 Olympics in Berlin

Another element of 20th Century history is that of media synchronicity, something not in living memory of a growing number of adults now. Certain things used to be televisual events that were simultaneously watched by viewers all over the world. The moon landing is the quintessential example of this but there are others, the Kennedy assassination, the fall of the Berlin Wall. Perhaps the last one of these was 9/11. There used to be a shared consumption of media, not these atomised one:one relationships we have with screens today. It’s like this died with the 20th century which is both the period V’s allegory is based on and the period of history in which the show was made. V itself was a televisual event.

After social media these experiences were less and less shared as bubbles of people form around different opinions not just about politics or religion but on the very parameters of reality itself. V was made before this, and there are many scenes of people gathering around televisions as if they are campfires around which we share a communal experience. This phenomenon is now a historical artefact.

V’s message was that there was a danger of that simultaneous reception of media, that shared experience could be corrupted. Someone like Riefenstahl could manipulate it to disseminate powerful lies. Whereas I think the current danger is that any sense of shared narrative is completely lost threatening our grasp on reality.

Leni Riefenstahl later claimed to have been disappointed by how her films were used, but she was clearly seduced by the power and the force of the Nazis as she depicted them in her films. Just as we see Kristine is seduced by the magnetism and dark sexuality of Visitor deputy commander Diana – another thing that is rather unsubtly implied less so than the relationship between Eleanor and Steven. Riefenstahl is also guilty of a willful ignorance about the atrocities committed by the Nazis in much the same way that Kristine is clearly selective about what she sees in the Visitors.

The tide turns for Kristine Walsh when she is directly confronted with the ugly truth.

But Kristine Walsh’s story is also one of redemption as she slowly starts to become increasingly unsettled by her new masters. Beneath their superficial charm and goodwill even Kristine begins to register more and more disturbing facts about them that even she cannot block out. The final nail in that coffin is most likely the discovery of Mike Donovan’s son Sean down in the cool stores where the bodies of thousands are held for consumption later. This leads to a massive change of heart at the gala event at the Medical Centre. After Juliet Parrish unmasks John on international television Diana sends Kristine to go on camera to sell what has happened as fake news. She does not. In what I think is a last minute decision she makes a stunning turn and tells the audience “this is real!” She must know what is going to happen, and she courageously continues to speak even as Diana is shooting at her.

I also can’t help feeling there is an eerie coincidence in the choice of the name Kristine. Christine Chubbock was a journalist who famously committed suicide on air. Chubbock did this for personal reasons but I can’t help be struck by the coincidence that Kristine Walsh also commits a form of suicide by deciding to finally speak the truth.

This is the redemption of the Kristine Walsh character, a final act of bravery in an impressive and very public about-face.

It’s a hopeful message that collaboration doesn’t have to fully define us. You can choose to be something else. It’s never too late to do the right thing.

How fitting that Kristine’s end is witnessed on the screen behind Diana as she takes aim at the broadcaster to put an end to her final act of defiance.

Safe journey Kristine, wherever you’re going.

*You really didn’t ask, but of course I must add here my opinion of Jojo Rabbit as an historian. I love Taika Waititi’s work and I love history. And I can generally put aside historical accuracy if a film depicts a truth of some sort, which Jojo Rabbit does. Kind of like in The Crown, which does this in every single episode. For example in the Tywysog Cymru episode we know Prince Charles didn’t literally get up and make explosive comments in favour of Welsh nationalism in Welsh at his investiture in Aberystwyth, but the episode captures the spirit of his change in attitude to Wales having formed a bond with his tutor Welsh Nationalist Edward Millward. Similarly Jojo Rabbit captures the essence of the worst excesses of the Third Reich which to me is a truth of a kind even if things literally did not happen to any specific individuals. Just like V which doesn’t literally tell the stories of specific resistance fighters but tells their truth. But Jojo Rabbit has problems creatively for me, mainly with tone and bite. Waititi revels in telling stories with childish naīveté. This approach softens the blow of the criticisms his films deliver. This works well for a Māori community on the East Cape but maybe not so much in Nazi Germany.